Secondary Dominants

And now for something completely different:

The strongest characteristic of dominant resolution is root motion down a perfect fifth.

The "primary" dominant in all major keys is the V chord. For example:

V7/I (pronounced, "five-seven of one"), in the key of C major is a G7 chord and it

naturally "wants to" resolve down a fifth to the tonic, a C major chord. One hears this

cadence (point of rest) in classical music all the time.

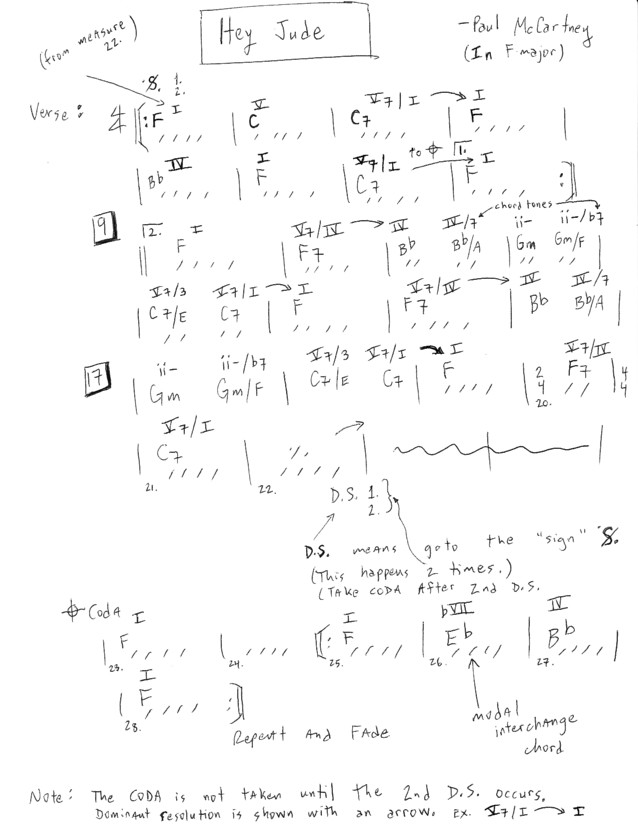

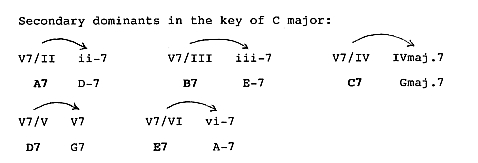

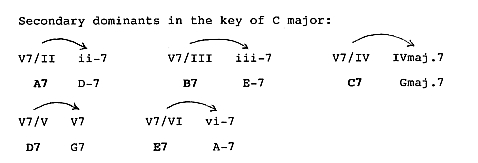

A secondary dominant is V7 of any diatonic chord other

than the I chord. For example: V7/II, V7/III, V7/IV, V7/V, and V7/VI are all secondary

dominants. Consult the following diagram:

All secondary dominants share the following 4 characteristics:

All secondary dominants share the following 4 characteristics:

- They are a perfect fifth above their target chords.

-

They are non-diatonic structures. (At least one of their chord

tones is NOT in the key.)

- They are expected to resolve to a diatonic chord a perfect fifth below.

-

They are built upon a diatonic root. (This is why V7/VII in a major key

is not used. The root a perfect fifth above vii-(b5) is NOT diatonic.

For example: In C major, a perfect fifth above B-7(b5) is F#. F# is nondiatonic

to the key of C. Also, V7/VII is not used in a major key because dominant

resolution to a min.7(b5) chord sounds very "unstable" or "awkward." Also note,

secondary dominants never resolve to diminished 7th chords for the same reason -

it would sound too "weird."

Another thing worth mentioning... secondary dominants can occur in both major keys as well as minor keys.

You may be asking yourself, "Why all these rules?" or rather, "What's the purpose of these secondary

dominants?" and those are perfectly valid questions. In short, secondary dominants sound good.

They are a nice way of adding variety to ordinary diatonic chord progressions. In fact, they create

a kind of temporary key change (without actually modulating) and help drive the music forward, as is

characteristic of dominant 7th chords. Dominant 7th chords sound "unstable." They "want" to be

resolved!

For example, in the key of C, instead of playing a "C" going to an "Am" chord, you could play

C => E7 => Am. In this context, the "E7" chord creates a kind of musical tension that "yearns" for

resolution. Resolving "E7" down a perfect 5th to an "Am" chord brings this resolution by creating

a nice little cadence (point of rest). We temporarily hear "Am" as being a "new" root.

Song writers will be interested in knowing about these chords. Look at some of your

songs and experiment with trying to add some secondary dominants - you may just transform

a tune that's "pretty good" into something that is much "cooler" and/or "catchier."

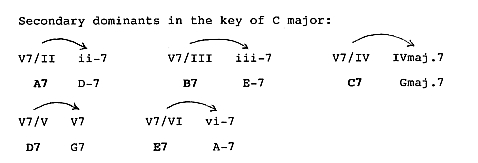

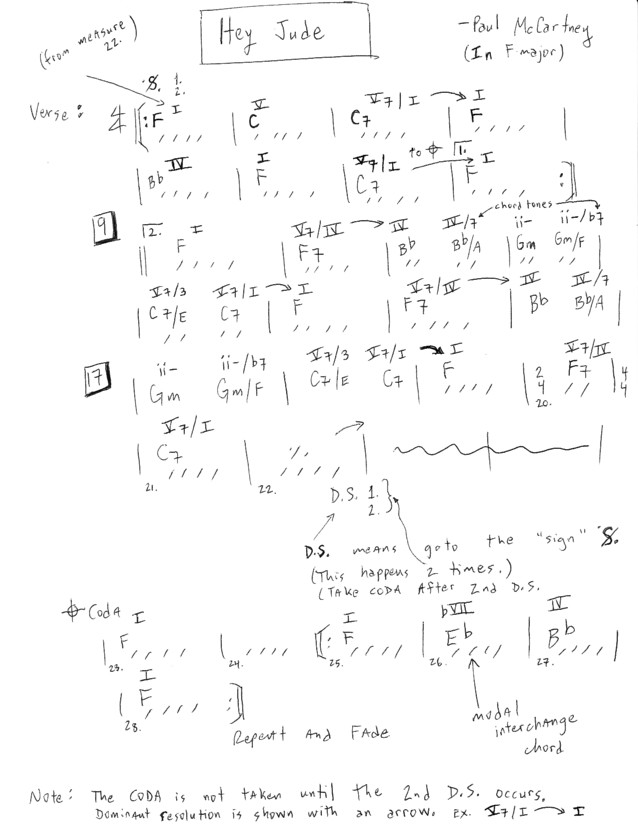

What follows is a harmonic analysis of the Beatles tune, Hey Jude. It's a fine example

of how to use secondary dominants effectively. Enjoy.