Jon Damian's Palette - Three Note Motifs

Introduction

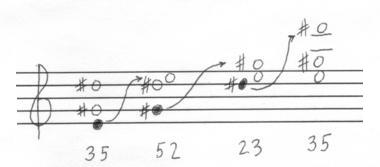

This is a picture that Jon Damian drew for me a long time ago in one of our lessons. Jon simply

calls this image the "palette" or "3 note motifs." Jon recently wrote a great book called,

The Guitarist's Guide to Composing and Improvising, where he explains this interesting

image and presents many excellent ideas for the improvising guitarist. I highly recommend that

you buy Jon's book and read it. It will definitely open your mind to new ways of thinking about

music and playing the guitar.

In short, Jon's book is a real jem chock full of great knowledge, but I won't kid you. It will make

you work very hard, but that's to be expected as anything worth while is not easy. An interesting

thing about the palette, for instance, is that it is deceptively easy to present and understand, yet

takes a lifetime to master and integrate into your playing. I'm still working on it. The applications

are limitless, but I will try my best to get you started.

The Palette

For starters, a motif is just a little melodic idea that can be varied

and repeated and so on. The palette depicts 36 possible ways to play 3 note motifs on the guitar. These 36

motifs fall into 6 main sound catagories:

- clusters - which are notes that don't really form any sort of chord

- triads (open and closed) - the foundation of western harmony

- quartals - voicings in 4ths (very jazzy sounding structures)

- 7th chords with no 5th

- 7th chords with no 3rd

- octaves - voicings that are an octave in height

Each number on the drawing represents a diatonic interval for some parent scale of your choice. For

instance, the number 2 anywhere on the drawing represents a diatonic 2nd, the number 3 a diatonic 3rd,

and so on.

The best way to explain how the palette works is to just show you some examples. After a few,

I think you'll get it. I have chosen E major as the parent scale to work as a basis.

3 5 - 7th chords with no 5th:

The numbers 3-5 represent the 3 note motif with a diatonic 3rd between the first and second note of the motif

and a diatonic 5th between the second and third note of the motif. If we pick E as the starting note and

work our way up the E major scale using this motif we get the following structures:

- (e, g#, d#)

- (f#, a, e)

- (g#, b, f#)

- (a, c#, g#)

- (b, d#, a)

- (c#, e, b)

- (d#, f#, c#)

Play these voicings in as many ways as you can on the guitar. Be sure to consult

Lesson 7

to refresh your memory if you are having trouble recalling the shapes of intervals.

Inversions: The 3-5 structure yields root position 7th chords with no

5th when we use a major scale as our parent scale basis. Now, if we were to invert these strutures,

that is, place the bottom note up one octave in each voicing, we transform the 3-5 motif into the 5-2

motif. If we invert the 5-2 motif, we get the 2-3 motif. Invert the structure one more time and we

come back to the 3-5 motif. The structures are cyclical in nature. That is, they repeat. I find this

extremely interesting. Don't you?

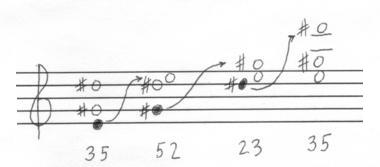

Consult the following diagram to see what I mean. Also, be sure to consult the palette to see how

this cyclical relationship is depicted.

(Emaj.7 Using the 3-5, 5-2, and 2-3 Motifs)

7 4 - 7th chords with no 5th:

The numbers 7-4 represent the 3 note motif with a diatonic 7th between the first and second note of the motif

and a diatonic 4th between the second and third note of the motif. Again, let's pick E as the starting note

and work our way up the E major scale using this motif to get the following structures:

- (e, d#, g#)

- (f#, e, a)

- (g#, f#, b)

- (a, g#, c#)

- (b, a, d#)

- (c#, b, e)

- (d#, c#, f#)

Again, we can invert the 7-4 motific structures in the same way as we did with the 3-5 motific structures.

In doing so, we get the following cycle of motifs:

-

7-4 ==> 4-6 ==>

6-7 ==> 7-4

As you might have suspected, there is an intimate connection between the 7-4 and 3-5 motifs - they

both represent 7th chords in root position. However, the 3-5 structures have notes arranged more closely

together than the 7-4 voicings. In fact, this trend is true throughout the palette within each of the

6 sound catagories. That is, for each tightly voiced motif there is an analogous version of it with a more

spread-out voicing. You can consider the "octaves" group to act as a kind of dividing line between these

two large groups of motifs on the palette.

For instance, if you look at the palette, motifs to the left and above the "octaves" group are generally more

tightly packed together than motifs to the right and below the "octaves" group. And just to make sure

we're on the same page, the "octaves" group contains the following 6 motifs: 2-7, 3-6, 4-5, 5-4, 6-3,

and 7-2. (Notice how the two numbers in each motif in the "octaves" group add up to the number 9.)

Actually, if you look even more closely at the "octaves" group, you will see that the 3 left motifs

(2-7, 3-6, and 4-5) mirror the 3 right motifs (5-4, 6-3, 7-2). (I just noticed this myself right now.

Like I said in the introduction to this lesson, this stuff is deep and you can learn from it for the

rest of your life.)

Here are some examples of tighly packed motifs and their analogous spread-out versions:

- 3-3 is analogous to 6-6 ==> root position triads

- 4-4 is analogous to 7-5 ==> quartals

- 2-6 is analogous to 3-7 ==> clusters

These analogous pairs are not always obvious.

So now what? I encourage you to pick a major scale and work your way through each

motific pattern. Be sure to play the inversions of each motif and try to hear their similar sound characteristics.

This will take some time as you can imagine, but there are so many cool voicings hiding out in these patterns. All

you have to do is apply yourself to find them.

After you've finished with a major scale, try a melodic minor scale and then harmonic minor scale as your basis.

(Give yourself about 10 years to complete this exercise. I'm still working on it.)

Also, be sure to draw all the voicings using tableture diagrams and try to integrate as many of these patterns as you

can into your playing and your favorite tunes. Some will be more useful than others, but it's really up to the

application and musical context and so on.

And finally, be sure to read Jon Damian's book to get some ideas

as to how he uses these voicings. And of course, if there are things you discover about these motifs

that you would like to share with me, please be sure to

email me and let me know. I would love to

hear from you. Good luck!