Position Playing in a Nutshell...

Position playing is pretty straight forward. There's not too much to it really, only a few rules. So here they are:

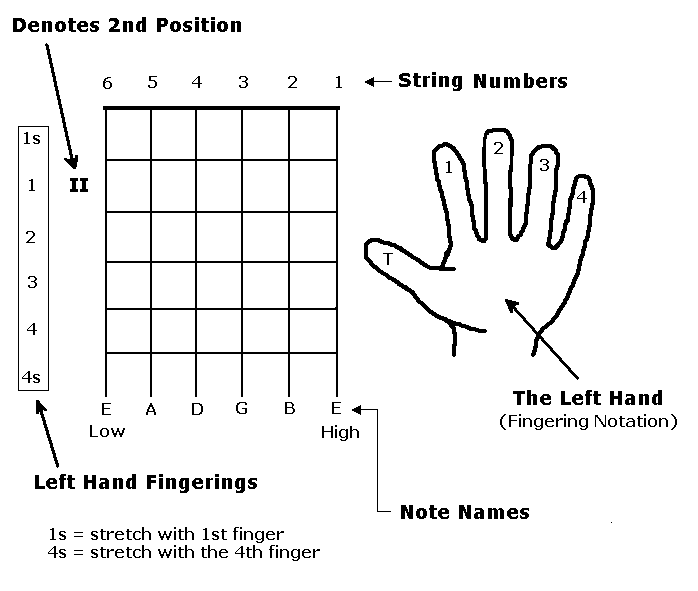

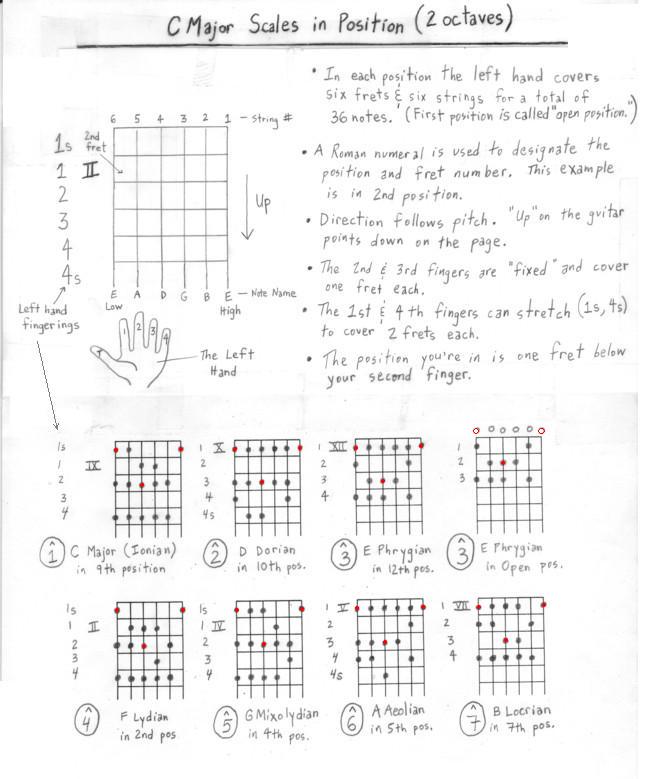

- In each position the left hand covers 6 frets and 6 strings for a total of 36 notes.

- A Roman Numeral is used to designate the position and fret number. The diagram below is in second position.

- The 2nd and 3rd fingers are "fixed" and cover one fret each.

- The 1st and 4th fingers can stretch (1s, 4s) to cover 2 frets each.

- The position you're in is one fret below your second (middle) finger.

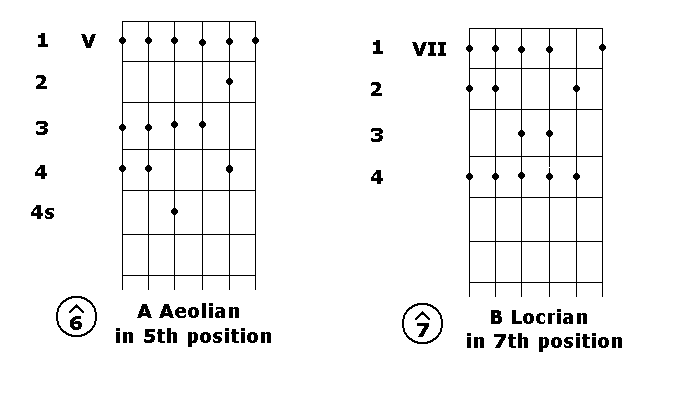

7 Patterns for C Major Using Strict Position Playing Rules...

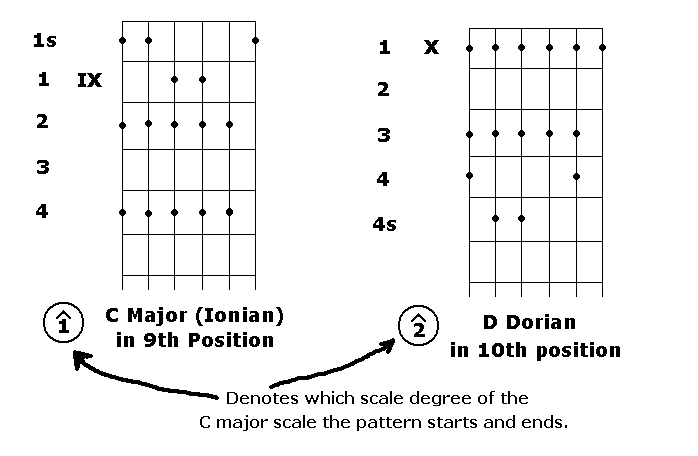

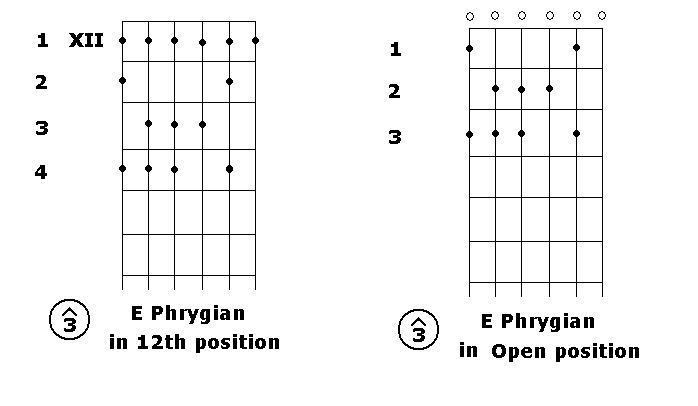

Without further ado, here are the 7 patterns for a C Major scale using strict position playing rules and fingerings. You will notice that for one of the patterns (E Phrygian) I have drawn the pattern twice - once in 12th position and once in open position. I want you to be able to cover the entire neck of the guitar. That is, I want you to see how this pattern wraps on the guitar. Also, down below I'll explain what the Greek names mean. (Ionian, Dorian, etc.) Read on.

NOTE: In these diagrams the numbers with the little caret symbol (^) enclosed in a circle above mean scale degree. What I'm illustrating here is that each pattern starts at some scale degree of C major. For instance, the first pattern, C Major (Ionian), starts at the first scale degree (or note) of the C major scale. The second pattern, D Dorian, starts at the second scale degree and so on.

Since we've got 7 notes in a major scale, we've got 7 patterns for C major where each pattern's lowest note starts at a different scale degree. With these 7 patterns, we move up the neck of the guitar positionally until the patterns start to repeat an octave higher.

7 notes, 7 patterns. Cool.

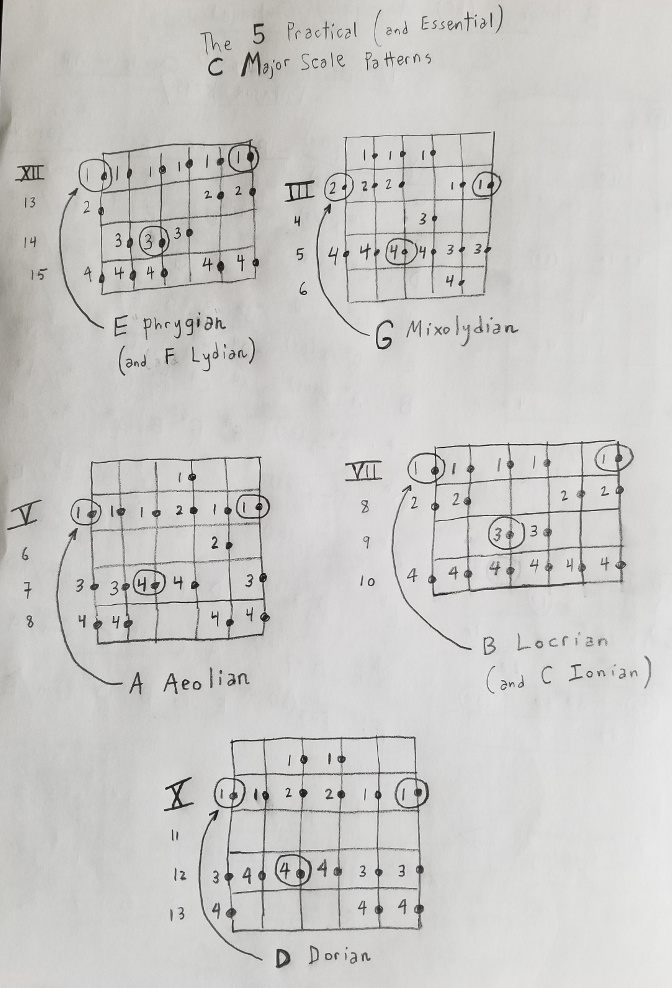

5 "Practical" Patterns For C Major...

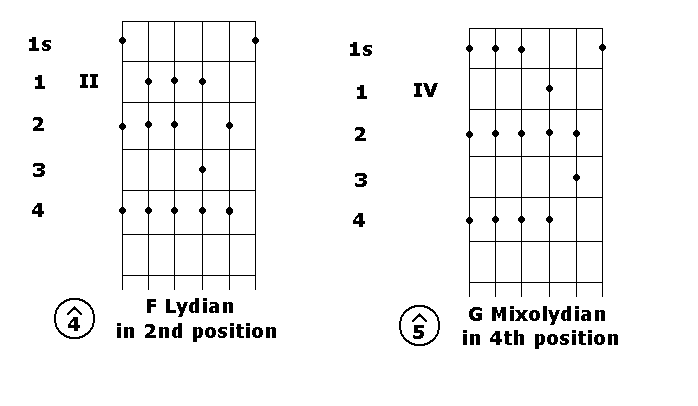

In addition to the above fingerings, there are some other useful fingerings and they may seem more "natural" to you than some of those 1st and 4th finger stretches above.

The following 5 patterns are very useful and I would go so far as to say that they are essential. Two of the patterns are already found above (Phrygian and Locrian) but the other three (Mixolydian, Aeolian and Dorian) break strict position playing rules to accommodate an easier way to play their respective patterns.

Check it out:

Note how the Phrygian pattern above is also used to play Lydian and that the Locrian pattern is used to play Ionian. This is why we have 2 less patterns compared to the strict position patterns above: some doubling-up occurs. For instance, if you want to play F Lydian, use the E Phrygian pattern but start that pattern with your 2nd finger on the low E string. You can do the same thing when playing C Ionian by using the B Locrian pattern.

BREAKING THE RULES: Notice how I make use of the 4th finger to pivot into a lower position on the next higher string in the Aeolian and Dorian patterns when ascending the scale in those patterns?

For instance, in the Aeolian pattern, I play the "A" note on the D-string (at the 7th fret) with my 4th finger instead of my 3rd. This helps me get into place to play the "B" note more easily on the G-string with my first finger at the 4th fret instead of staying on the D-string and playing that "B" with my 4th finger.

We perform a similar maneuver when playing D Dorian. In both cases, we've violated (sidestepped?) strict position playing rules to make things a little easier for us.

Major Scale Modes...

Ok, firsts things first. The subject of modes can cause some confusion for some students and, honestly, I really don't know why. Perhaps, it's just in the presentation of the subject. For me, when I first learned about modes, my playing just opened up. Things started to make sense. A lot of sense. In an effort to lessen the confusion some folks may have about this subject, here's my attempt at explaining it. But first, let me just say a few more things about the scale patterns above.

- All of the patterns above are fingerings for natural notes on the guitar. Reread the previous sentence and think about this idea for a moment.

- All of these patterns can be thought of as a "C major" scale. That is to say, a C major scale contains only natural notes. So, any of these patterns can be used when you want to play a C major scale anywhere on the neck of the guitar.

- The idea in the previous point implies that all of these patterns can also be thought of as a D Dorian scale, or an E Phrygian scale too. Why? Because all of C major's modal derivative scales also contain only natural notes.

There are two ways to approach learning (and thinking about) modes - the derivative and the parallel approach. In this lesson, I am only going to explore the derivative approach and it basically means this: There are 6 other scales "hiding out" inside a major scale. A nice way to get at this concept of "derivative-ness" is to ask yourself the following question: "What other scales can be derived from a major scale without changing any notes in that major scale?" If you understand the answer to this question then you understand modes from the "derivative approach" perspective.

So here's my version of the answer. Now, my answer is a bit long winded, so bear with me. Try to be patient.

Answer Part 1 - The Relativity of a Tonal Center...

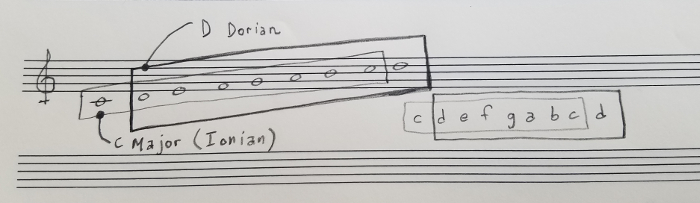

If we start a C major scale at the 2nd scale degree and play (only natural notes) up to the next D note one octave higher we get a minor sounding scale that is called D Dorian, which is not the same as a C major scale.

This minor sounding scale contains the following natural notes: D, E, F, G, A , B, C, D. This may seem a little odd to you. How can a scale that has all natural notes *NOT* be C major? Or, how can these 7 notes be more than one scale? Can it be both C major and D Dorian?

The answer is lies in how we hear those natural notes. That is, the natural notes will sound (or function) differently under different harmonic contexts in which they are played.

So, let's play.

Play the first 8 notes of the second pattern above, the one in 10th position labeled "D Dorian."

Listen to this scale.

Start at the lowest note and slowly proceed until you reach the highest note, but only play the first 8 notes. Now, slowly descend playing one note at a time and listen carefully.

Does this scale sound like a C major scale? No, and the reason why is because by starting and ending the scale on a D note, we establish that note as sounding like the root (or tonal center) for the scale. This means that the other notes are heard relative to this D root!

This is strange indeed. One minute I'm telling you that the pattern you just played is a C major scale and now I'm telling you that the pattern is also a D Dorian scale. And indeed, that is exactly what I mean to say. The important thing to understand is that the 7 natural notes will sound like a major scale if they are played in such a way as to make them sound like a major scale or they will sound like one of the modes if they are played in such a way as to make them sound like one of the modes. So it all boils down to how you go about establishing a tonal center for the notes you want to play.

Answer Part 2 - Establishing a Tonal Center...

Establishing a tonal center can be done in a few different ways.

-

Play a single chord for a long time. The root

note of the chord is the tonal center.

In this example, a piece called

Arrival, I only play

one chord throughout the entire song, an E major (add 9)

chord. E is the "tonal center" or "root note" for the entire song

and all melody notes are heard against this root.

Listen to my piece called Arrival. I only play one chord throughout the entire song, an E major (add 9) chord. E is the "tonal center" or "root note" for the entire song and all melody nodes are heard against this root. - Play the same pedal-tone (bass note) over a bunch of different chord changes. The lowest note establishes a strong tonal center. An ideal example illustrating this idea is the Pink Floyd tune "Careful With That Axe, Eugene." Roger plays D notes (roots and octaves) while Dave and Rick play Dm and Em chords on top of Roger's bass notes.

- Play drone notes. This is what is done in classical Indian music. An instrument called a tambura plays only roots and 5ths (in the low to mid range), while other instruments play around this tonal center.

- Play notes in such a way as to bring out a tonal center. In other words, make one particular note sound like the root. (This can take years of practice, but it is not impossible to learn.)

Answer Part 3 - A Playing Exercise...

Record yourself playing a C major chord for a few minutes. Then record yourself playing a Dm chord for a few minutes. Now, pick any one pattern above and solo over the C chord. Then using the same pattern, solo over the Dm chord.

In both cases, you are playing the same notes, but they sound like different scales because the context in which you played them changed. That is, the tonal center changed from C major when playing over the C chord to D dorian when playing over the D minor chord.

This is an important concept to understand and if this makes sense to you and if you can hear it, then I have succeeded in explaining to you the "relative-ness" that is found in music.

It all depends on where you stand or your frame of reference. And where you stand depends on how you hear the tonal center for a particular instance of time.

Getting this concept (derivative thinking) involves two levels of understanding:

- You need to understand the relative-ness of music. For instance, starting a major scale at the second scale degree produces a scale we call "Dorian". This is an intellectual idea.

- You have to be able to hear the relative-ness of music. You can hear how natural notes over a D minor chord sound different when they're played over a C major chord, for instance. This is a physical thing.

If you can do these two things, then you "get it". This insight, combined with this ability of hearing, is vital. And really, it's the basis for understanding improvisation. That's why I highly recommend you do the playing exercises for this lesson (and all lessons in this series).

Turns out the best way to learn how to play the guitar is to play the guitar. You'd be surprised how this most basic and obvious idea is overlooked by people aspiring to learn how to play.

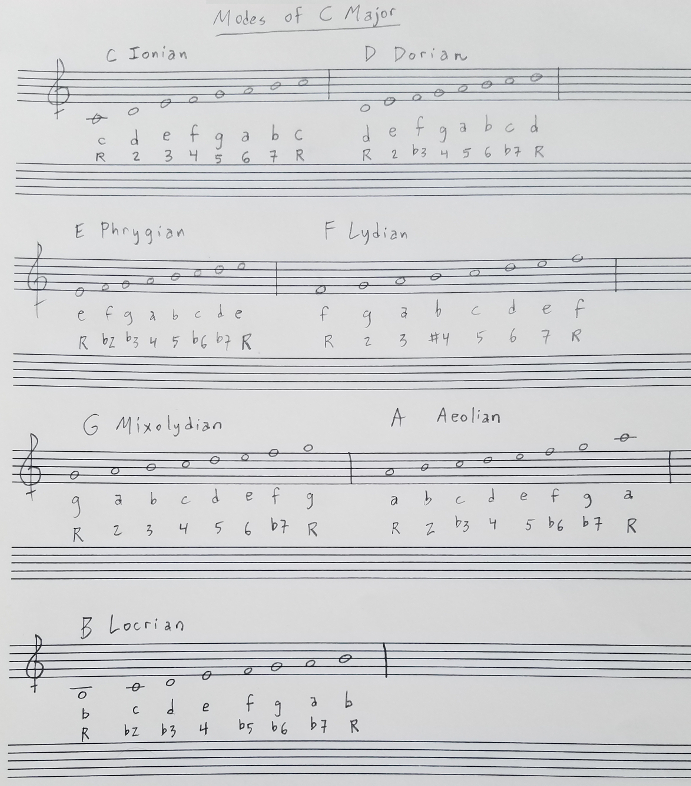

Derivative Modes in C Major... Any Colour You Like

Let's spell it all out. Let's continue down our path of "derivative thinking" and make each note of a C major scale be the root and see what scales we come up with. We'll start with C just for good measure, and then go up each scale degree and see what we get until we hit the seventh.

- Starting a C major scale at the 1st scale degree yields a major sounding scale called C Ionian. It contains the following notes: C, D, E, F, G, A , B, C.

- Starting a C major scale at the 2nd scale degree yields a minor sounding scale called D Dorian. It contains the following notes: D, E, F, G, A , B, C, D.

- Starting a C major scale at the 3rd scale degree yields a minor sounding scale called E Phrygian. It contains the following notes: E, F, G, A , B, C, D, E.

- Starting a C major scale at the 4th scale degree yields a major sounding scale called F Lydian. It contains the following notes: F, G, A , B, C, D, E, F.

- Starting a C major scale at the 5th scale degree yields a major sounding scale called G Mixolydian. It contains the following notes: G, A , B, C, D, E, F, G.

- Starting a C major scale at the 6th scale degree yields a minor sounding scale called A Aeolian which is also called A Natural Minor. It contains the following notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A.

- Starting a C major scale at the 7th scale degree yields a minor sounding scale called B Locrian. It contains the following notes: B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B.

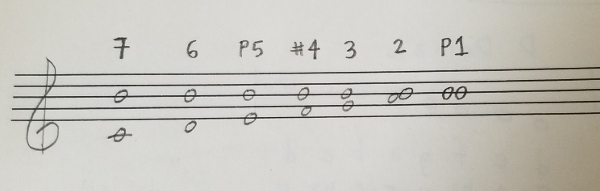

As you can see from the image above, I've written out all of the derivative modes for C major. You can say that these modes are relative to the key of C major. That is, all of these modes have the same notes, natural notes, and are diatonic to each other.

I've also provided an intervallic analysis for each note in each mode, so you can see how each note functions (or sounds) in that mode.

For instance, F Lydian has a #4 in its scale formula, the B note, which means B functions as a raised 4th in a Lydian context (or over an F bass note or F major chord). But, we can also see that B functions as a major 7th in a C major context (or over a C bass note or C major chord) or as a major 6th in a D Dorian context, etc.

In each case, that same B note creates a different interval over each of the different bass notes (or chords).

What are the implications of this?

If a note gets a different numerical analysis it will have a different interval ascribed to it which means it will both function and sound differently as the context in which it is heard has changed.

In a later lesson, Modes - The Parallel Approach, I go into much further depth about each mode's intervallic structure or formula. We call that topic, the "parallel approach" where the word "parallel" means "same root". In that lesson we compare parallel scales, or scales with the same root, to each other to gain some insight. But, don't worry about that stuff for now. We'll get to it later.

How Modes correspond to Triads in a Major Key (C Major)...

Now, if you haven't put this together yet, the chords (or triads) associated with each mode are the same chords that are diatonic to the major key you're working in. In the case of the key of C major, the triad that corresponds to:

- C Ionian is the "one chord" or a C major triad ==> I, "one major"

- D Dorian is the "two chord" or a D minor triad ==> ii-, "two minor"

- E Phrygian is the "three chord" or an E minor triad ==> iii-, "three minor"

- F Lydian is the "four chord" or an F major triad ==> IV, "four major"

- G Mixolydian is the "five chord" or a G major triad ==> V, "five major"

- A Aeolian is the "six chord" or an A minor triad ==> vi-, "six minor"

- B Locrian is the "seven chord" or a B diminished triad ==> vii°, "seven diminished"

More Playing Exercises...

Now play each mode for 5 minutes or so by altering the tuning on your guitar. Use any of the patterns above or just play horizontally (up and down on one string at a time). Play only natural notes throughout this entire exercise. In each case, use the root note of the scale as a pedal tone. The nice thing about this exercise is that you don't have to record yourself to do this exercise. Just use the low strings on your guitar as pedal tones.

- C Ionian ==> Drop your low E to a low C.

- D Dorian ==> Drop your low E to a low D.

- E Phrygian ==> Use standard tuning and your low E string as the pedal tone.

- F Lydian ==> Raise your low E string a half-step to an F.

- G Mixolydian ==> Drop your A string a step to a G and use it as your pedal tone.

- A Aeolian ==> Use standard tuning and your A string as the pedal tone.

- B Locrian ==> Drop your low E string to a low B or raise your A string to a B.

One More: Record yourself playing diatonic chords in the key of C major. That is, for 3 to 4 minutes, record yourself playing a C major chord. Then record yourself playing a Dm chord for 3 or 4 minutes. And then an Em chord and so on up to a B diminished chord. Now, solo over each chord using the scale fingerings illustrated above. This is perhaps the best and most direct way to hear the 7 different modes that can be derived from the C major scale.

Putting It All Together...

Hopefully you aren't confused at this point. If you are, then I recommend that you reread the above sections and be sure to do the playing exercises. That's where your real learning will take place.

Now, let's try to gain some more understanding by looking at some examples outside the key of C. Remember, it's really important to be able to do this kind of calculus ==> using a major scale to think derivatively, that is, use a major scale to compute its relative modes. NOTE: One should also be able to go backwards, the other way ==> given a mode, be able to figure out its relative (or parent) major scale/key.

- Starting a major scale at the 2nd note yields a Dorian scale. For example, if you want to play a G Dorian scale, play an F major scale starting at the 2nd scale degree.

- Starting a major scale at the 3rd note yields a Phrygian scale. For example, if you want to play a B flat Phrygian scale, play a G flat major scale starting at the 3rd scale degree.

- Starting a major scale at the 4th note yields a Lydian scale. For example, if you want to play an E Lydian scale, play a B major scale starting at the 4th scale degree.

- Starting a major scale at the 5th note yields a Mixolydian scale. For example, if you want to play an F Mixolydian scale, play a B flat major scale starting at the 5th scale degree.

- Starting a major scale at the 6th note yields an Aeolian scale. For example, if you want to play a C Aeolian scale, play an E flat major scale starting at the 6th scale degree.

- Starting a major scale at the 7th note yields a Locrian scale. For example, if you want to play an G# Locrian scale, play an A major scale starting at the 7th scale degree.

At this point, I hope things are starting to make sense, but if not, here is a chart that summarizes all the modes for all of the major scales. It's a variation of the chart that was presented at the end of Lesson 6.

| The Major Scale Modes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode: | Ionian | Dorian | Phrygian | Lydian | Mixolydian | Aeolian | Locrian | Ionian |

| Triad: | I | ii- | iii- | IV | V | vi- | vii° | I |

| The Natural Key: | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| Sharp Keys: | ||||||||

| G | A | B | C | D | E | F# | G | |

| D | E | F# | G | A | B | C# | D | |

| A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# | A | |

| E | F# | G# | A | B | C# | D# | E | |

| B | C# | D# | E | F# | G# | A# | B | |

| F# | G# | A# | B | C# | D# | E# | F# | |

| C# | D# | E# | F# | G# | A# | B# | C# | |

| Flat Keys: |

||||||||

| F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | |

| Bb | C | D | Eb | F | G | A | Bb | |

| Eb | F | G | Ab | Bb | C | D | Eb | |

| Ab | Bb | C | Db | Eb | F | G | Ab | |

| Db | Eb | F | Gb | Ab | Bb | C | Db | |

| Gb | Ab | Bb | Cb | Db | Eb | F | Gb | |

| Cb | Db | Eb | Fb | Gb | Ab | Bb | Cb | |

An Old Drawing...

Finally, here's an image of a drawing I made many years ago. It's what I used to base some of the charts on above in the beginning of this lesson. I think it's pretty cool, so I'm going to include it here for posterity's sake.

I encourage you to make your own drawings like this one. Create your own guitar journal, if you will. Go buy a nice hard-covered blank book without any lines in it and start drawing all the chord and scale diagrams you've learned. Drawing these things will help you learn them even better and it's a nice thing to have to refer to without having to look at a computer, etc.

Go to the next lesson, Lesson 14, or go back to the main menu.